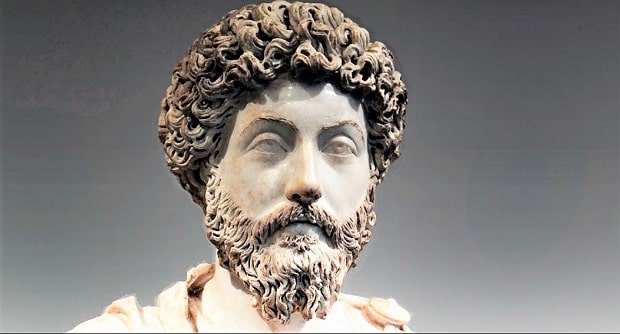

Marcus Aurelius also is known as Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus (Born on April 26, 121, in Rome – Died On March 17, 180, in Vindobona or Sirmio) was emperor of the Roman Empire from the year 161 to the year his death in 180.

He was the last of the so-called Five Good Emperors, third of the emperors of Hispanic origin, and is considered one of the most representative figures of philosophy stoic. Marco Aurelio and Lucio Vero were adoptive children of Antoninus Pius by the mandate of Adriano and the first two that prevailed jointly in the history of Rome.

His government was marked by military conflicts in Asia against a revitalized Parthian Empire and Upper Germania against the barbarian tribes settled along the Limes Germanicus, in Gaul, and along the Danube. During the period of his empire, he had to face a revolt in the eastern provinces led by Avidius Cassius, which he crushed.

Marcus Aurelius’ great work, Meditations, written in Hellenistic Greek during the campaigns of the 170s, is still regarded as a monument to perfect government. It is usually described as “a work written exquisitely and with infinite tenderness.”

Quick Facts: Marcus Aurelius

- Born: 26 April 121, in Rome

- Also Known As: Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus

- Known For: Stoic philosopher and The Emperor of the Roman Empire

- Reign: 8 March 161 – 17 March 180

- Predecessor: Antoninus Pius

- Successor: Commodus

- Co-emperor: Lucius Verus (161–169), Commodus (177–180)

- Parents: Father – Marcus Annius Verus, Antoninus Pius (adoptive). Mother – Domitia Lucilla Minor

- Dynasty: Nerva-Antonine

- Spouse: Faustina the Younger (m. 145)

- Children: Commodus, Lucilla, Marcus Annius Verus Caesar, Vibia Aurelia Sabina, Titus Aelius Aurelius, Fadilla, Gemellus Lucilla, Titus Aelius Antoninus, Hadrianus, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor, Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, Domitia Faustina.

- Died: 17 March 180 (aged 58), Vindobona or Sirmium

- Burial: Hadrian’s Mausoleum

Early Life of Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was born on April 26, 121 AD, to Marcus Annius Verus III and Domitia Lucilla. His name at birth may have also been Marcus Annius Verus just like his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather but, to avoid confusion, we’ll just call him Marcus Aurelius from the start.

His family was wealthy and relatively influential. According to Cassius Dio, one of our main sources for the reign of Marcus Aurelius, his family was somehow related to Emperor Hadrian. Aurelius’s father was a politician who held the office of praetor, but he died young when Marcus was just a child.

We’re not sure on the exact date, but it would have been around 124 AD while he was still in office. After his father’s death, Marcus Aurelius and his sister, Annia Cornificia Faustina, were adopted by their paternal grandfather, Marcus Annius Verus II, who had been made patrician during the reign of Vespasian.

His father had been a praetor and his grandfather served three times as consul so, naturally, it was expected for Marcus Aurelius to follow in their footsteps. In 127 AD, when he was just six years old, he was enrolled in the equestrian order by the nomination of Emperor Hadrian himself.

Other than that, we do not have much information about the early years of the future emperor, apart from the names of some of his teachers such as Diognetus and Alexander of Cotiaeum. Later on, he was also tutored by Apollonius of Chalcedon, the man who introduced him to Stoicism, the philosophy that deeply influenced all aspects of his life.

Rise to Power

Marcus Aurelius was born during the reign of Hadrian, who had no children of his own. Therefore, when the emperor fell ill in 136 AD, he thought it would be a good idea to appoint an heir. He adopted Lucius Ceionius Commodus who, as emperor-in-waiting, took the name Lucius Aelius.

However, this turned out to be an ill-fated choice, as Aelius died at the start of 138 AD. Next up, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius as his heir, who became emperor later that same year after Hadrian died on July 10. As it happened, Antoninus was also Marcus Aurelius’s uncle as he married Faustina, his father’s sister.

Hadrian’s adoption of Antoninus came with a few conditions. In turn, Antoninus had to adopt the surviving son of his predecessor, a seven-year-old boy also named Lucius Ceionius Commodus, as well as his own nephew, Marcus Aurelius. All of a sudden, Aurelius was the eldest son of the emperor, which meant that he was next in line for the throne.

Some historians have speculated that this had been Hadrian’s intention all along, although why the emperor granted so much favor to Aurelius, we’re not really sure. Anyway, Antoninus was now the new Roman Emperor and, to strengthen the bond with his newly adopted son, he also had Marcus Aurelius marry his natural-born daughter, Faustina the Younger.

The two of them would go on to have 13 children together. Unsurprisingly, Marcus Aurelius’s position as heir apparent brought with it a lot of new promotions. He was first made consul in 140. He also became the head of the equestrian order, he joined the colleges of priests, he took up residence in the imperial palace and was made quaestor learn about the paperwork and oration that were needed to rule Rome.

Marcus Aurelius Emperor of Rome

Around 160 AD, Antoninus fell ill. He died the following year at his ancestral home in Laurium, ending what was then the second-longest reign of the Roman Empire after that of Augustus. A few days later, he was deified at the request of his sons.

In his book, Marcus Aurelius spoke very fondly of his adoptive father, saying that no other man had more influence on him as a youth. “The king is dead, long live the king,” as the expression goes. Antoninus was gone and Rome needed an emperor.

The Senate was ready to confirm Marcus Aurelius as the new sovereign, but something curious happened. Marcus Aurelius refused to take office unless his younger brother, Lucius Verus, was made co-emperor alongside him. It was unusual, but the Senate accepted and March 8, 161 AD, marked the first time that the Roman Empire was ruled by two men.

That being said, it was never in question who the true leader of Rome was. Besides the fact that Marcus Aurelius was the chosen heir, he was also the older sibling, he had experience helping Antoninus run the empire, and he was the only one with the title of Pontifex Maximus. Verus obeyed Marcus “as a lieutenant obeys a proconsul.”

You might think this is a setup for some kind of conspiracy, or betrayal, or even assassination down the line. That’s usually how these situations unfolded in ancient times, but we have here a rare exception. Despite their different personalities, the brothers stayed on good terms for the extent of their joint rule, and never did one of them try to usurp the other.

The War in Parthia

You might think that the rule of a calm, practical, and amiable man would mark a time of peace for the Roman Empire, but that was not to be. In fact, almost for his entire 19-year reign, Marcus Aurelius was involved in one conflict or another.

First up was the Parthian Empire, a mighty Middle Eastern faction that had been around since the 3rd century BC. This was not the first time that these two powers clashed. It seemed that every time the Parthians wanted to expand to the west, they eventually ran into the dominion of Rome.

This usually took the form of the Kingdom of Armenia, a land that acted as a buffer between the two empires who both wanted to install an Armenian king who served their best interests. The last time this happened was during the rule of Trajan.