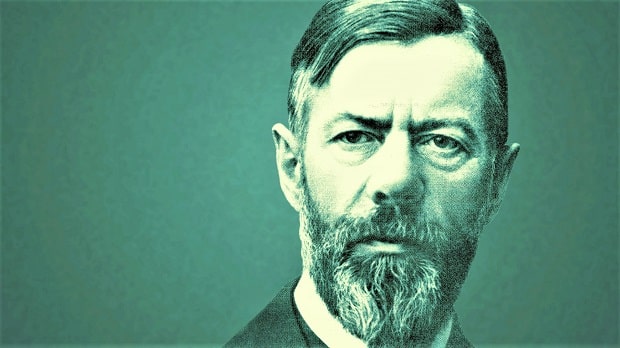

Max Weber (born April 21, 1864, in Erfurt, died on June 14, 1920, in Munich) was a German sociologist and economist. He is considered one of the classics of sociology as well as the entire cultural, social and historical sciences. With his theories and terminology, he had a great influence in particular on the sociology of economics, rule, and religion.

They are linked to his name“Protestantism-capitalism thesis”, the principle of “freedom of judgment”, the concept of “charisma” and the distinction between “ethical ” and “ responsible ethics”. Politics was not just a field of research for him, but as a class-conscious citizen and out of a liberal conviction, he expressed his commitment to the current political issues of the Empire and the Weimar Republic.

As an early theorist of bureaucracy, he was elected one of the founding fathers of organizational sociology via the detour of the US reception.

Quick Facts: Max Weber

- Born: Maximilian Karl Emil Weber on 21 April 1864

- Known For: sociologist and economist

- Parents: (Father: Max Weber Sr.), (Mother: Helene Fallenstein)

- Nationality: Prussia (1864–1871), German Empire (1871–1918), Weimar Republic (1918–1920)

- Spouse: Marianne Schnitger (1893–1920)

- Died: 14 June 1920 (aged 56) in Munich, Bavaria, Germany

- Quotes: “It is not true that good can follow only from good and evil only from evil, but that often the opposite is true. Anyone who fails to see this is, indeed, a political infant.” – Max Weber

The Early Life of Max Weber

Max Weber was born on April 21, 1864, in Erfurt, the first of eight children, six of whom (four sons and two daughters) reached adulthood. His parents were the lawyer and later member of parliament of the National Liberal Party Max Weber sen. (1836-1897) and Helene Weber, born Fallenstein (1844-1919).

His brother Alfred, born in 1868, also became an economist and university professor in sociology, while his brother Karl, born in 1870, became an architect. He was on the maternal line nephew of Hermann Baumgarten and cousin of Fritz Baumgarten and Otto Baumgarten.

Max Weber experienced a relatively intact family, “whose cohesion was manifested not least in disputes”. He was considered a problem child that at the early age of two years, meningitis was diagnosed. He asserted the rights of the firstborn early on; he felt himself to be the mediator of disputes between children and parents in the family.

He mastered the school requirements “effortlessly and with flying colors”. At the age of thirteen, he read works of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, Baruch Spinoza, and Kant, but also literary writers such as Johann Wolfgang Goethe.

Max Weber Education

Max Weber studied at the universities of Heidelberg, Berlin, and Gottingen, taking a special interest in law, history, and economics.

In 1882, Weber entered Heidelberg University as a law student. He joined the fraternity of his father and chose the field of law like him. Apart from these studies, he took economics classes and studied medieval history.

He had as teachers, among others, his uncle, the German liberal historian Hermann Baumgarten, author of two voluminous works on ancient and modern Spanish history and son and grandson of Protestant pastors. Additionally, Weber made extensive readings on theological topics.

He intermittently served in the German army in Strasbourg and, in the autumn of 1884, returned to his parents’ house to study at the University of Berlin. For the next eight years, Weber lived at his parents’ house, first as a student, then as an assistant in the Berlin courts and finally as a teacher at the university.

His residence at his parents’ house was interrupted only by a semester of study at the University of Göttingen and by occasional short periods of additional military training. In 1886 Weber passed the “Referendar” exams, which allowed him to practice as a lawyer.

In the late 1880s, Weber deepened his studies of history. He obtained a doctorate in law in 1889, with a thesis on legal history titled The History of Medieval Business Organizations. Two years later, Weber completed his Habilitation with the thesis on the Roman agrarian history and its significance for public and private law.

Having qualified – he was already able to practice as a Privatdozent – Weber was qualified in Germany to obtain a position as a university professor.

University and political Career

In 1892 he did his habilitation in Roman (constitutional and private) law and commercial law in Berlin with August Meitzen. Weber’s postdoctoral thesis was entitled The Roman Agricultural History in Its Significance for Public and Private Law.

A year later, in 1893, he was at the age of 29 years an associate professor of Commercial Law in Berlin. In the same year, he married his distant cousin Marianne Schnitger in Oerlinghausen, who later became active as a women’s rights activist, writer, and politician. There is much to suggest that the two have a so-called companion marriage led. The marriage remained childless.

Also in 1893, Max Weber was co-opted for the first time in the committee of the Association for Social Policy. This was preceded by the large empirical study on the situation of agricultural workers in East Elbe Germany, which appeared in the association’s publication series in 1892.

The club was one of Weber until his death. Weber belonged to the younger left-liberal generation of the association, not to the older generation of the so-called Catheter Socialists around Gustav Schmoller and Adolph Wagner.

In 1893 Weber also joined the All-German Association, which was a nationalist Represented politics. However, he left this organization in 1899 when he was unable to assert himself on the so-called “Poland question” with his demand for the closure of the borders for Polish migrant workers.

In his resignation letter of April 22, 1899, Max Weber expressly stated the question of Poland as the reason for his resignation and complained that the Pan-German Association had not called for the complete exclusion of the Poles with the same vehemence with which he advocated the expulsion of the Czechs and Danes.

In this respect failed Weber at this point because the peasant members of the Pan-German League, which overcoming the farmworkers lack presented to the fore, were able to assert their interests. Already in 1894, he got a chair for national economics at the Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg.

There he gave his inaugural address The Nation-State and Economic Policy on May 13, 1895, which was published in the same year. [18] In 1896 he accepted a call to the renowned chair of Karl Knies at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg.

Weber was a member of the Social Policy Association from the beginning of the 1890s until the end of his life. In the 1890s he was a member of the Evangelical Social Congress and supported Friedrich Naumann and the National Social Association he founded.

The Task of Teaching and Scientific Work

In 1898 Weber had to limit his teaching because of a nerve disorder diagnosed as neurasthenia. He hadn’t taught since 1900, and in 1903 he gave up his professorship. Until 1918 he lived as a private scholar on the interest income from family assets.

In 1904 Weber, together with Edgar Jaffe and Werner Sombart, took over the editing of the Archive for Social Science and Social Policy and thus resumed his journalistic work.

In the same year, he made a three-month trip to the United States, where he visited Protestant communities, Chicago slaughterhouses, Indian schools, and the Tuskegee Institute, and met the black scientist W.E.B. Du Bois; Impressions that led to Weber increasingly rejecting racially oriented explanations for historical and social contexts.

Weber had been intensively devoting himself to the conception of a large-scale new handbook, the layout of social economics, since 1909. Economy and society appeared posthumously in 1922 as his own contribution to this.

In 1909 he founded the German Society for Sociology (DGS) together with Rudolf Goldscheid and Ferdinand Tonnies, Georg Simmel, and Werner Sombart. Of great importance for the design of his social environment was the discussion circle, the so-called “Sunday Circle” (Marianne Weber), which took place after Weber’s Heidelberg move in 1910 to the grandparent’s “Fallenstein Villa” at Ziegelhauser Landstrasse 17.

Scientists, politicians, and intellectuals such as Ernst Troeltsch, Georg Jellinek, Friedrich Naumann, Emil Lask, Karl Jaspers, Friedrich Gundolf, Georg Simmel, Georg Lukács, Ernst Bloch, Gustav Radbruch, Theodor Heuss, and others. The so-called “Myth of Heidelberg” was founded not least by these meetings.

Sociology of Religion

Weber’s work on the sociology of religion opens with the essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and continues with Religion in China: Confucianism and Taoism, The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism and Ancient Judaism.

His work on other religions was interrupted by his death in 1920, pending the continuation of studies on ancient Judaism with the study of the psalms, the book of Jacob, the Talmud, early Christianity, and Islam.

His three main ideas about religion were: the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relationship between social stratification and religious ideas, and the unique characteristics of Western civilization. His objective was to find reasons that justify the difference between the development process of Western and Eastern cultures.

In analyzing his discoveries, he maintained that Puritan (and more broadly Christian) religious ideas had had a major impact on the development of the economic system of Europe and the United States, but stressed that these were not the only causes of development.

Among other causes that Weber mentioned we find rationalism in the scientific search, mixing observation with mathematics, systematic study and jurisprudence, rational systematization of government administration, and economic company.

In the end, the study of the sociology of religion, according to Weber, scarcely explored a phase of the emancipation of magic, that “disenchantment with the world” that he attributed as an important distinctive aspect of Western culture.

Max Weber Death

At the end of May 1920, Max Weber worked intensively on the corrections to the collected essays on the sociology of religion. At the beginning of June, Weber contracted pneumonia caused by the Spanish flu and had to cancel the lectures on “state sociology” and “socialism” that had just started.

He died as a result on June 14, 1920, in Munich-Schwabing, Seestrasse. The funeral service, at which Marianne Weber made a funeral speech, took place in the Munich East Cemetery, the later urn burial in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof with the participation of around a thousand people. Weber and his wife’s grave is located in Bergfriedhof, Heidelberg, Germany.

Max Weber Books

- The History of Medieval Business Organizations – (1889)

- Roman Agrarian History and its Significance for Public and Private Law – (1891)

- Condition of Farm Labor in Eastern Germany – (1892)

- The stock exchange – (1894 to 1896)

- The National State and Economic Policy – inaugural lecture at Freiburg University (1895)

- Collected Essays on the Sociology of Religion – (1920 to 1921)

- Collected Political Miscellanies – (1921)

- Rational and Sociological Foundations of Music – (1921)

- Collected Essays on Epistemology – (1922)

- Economy and Society – (1922)

- Collected Essays on Sociology and Social Policy – (1924)

- General Economic History – (1924)

- Sociology of the State – (1956)

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: whatinsider.com/max-weber-biography-sociology-capitalism-and-death/ […]