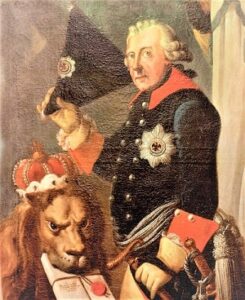

Frederick the Great or Frederick II (Born on 24 January 1712 – Died on 17 August 1786) was a 3rd Prussian king and military leader who ruled the Kingdom of Prussia from 1740 until 1786, at the age of 46 years, he was the longest-serving king of any House of Hohenzollern.

His most significant achievements during his reign included his military victories, his reorganization of the Prussian armies, his sponsorship of the arts and the Enlightenment, and his final success in the Seven Years’ War against the major European powers of the time.

Frederick was the last monarch Hohenzollern entitled King in Prussia and declared himself king of Prussia after achieving sovereignty over most historically Prussian lands in 1772. By the end of his reign, Prussia had greatly increased its territories and had become a true military power.

Almost all German historians of the 19th century regard Frederick the Great as the romantic model of a warrior to be given glory, as his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to the duty of government, and success in the building are praised. a Prussia capable of assuming a leading role in Europe.

He remains an admired and historical figure after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I; thus, Nazism glorifies him as the German leader who precedes the figure of Hitler. Frederick II was an enlightened and relatively progressive King for his time. He was a high leader of Freemasonry regular and decisively supported the Enlightenment.

He tried to give a twist to the Monarchy of his time. However, being succeeded by his nephew, a religious conservative, the enlightened project comes to a halt. Militarily he was brilliant and very aggressive. But unlike the authoritarianism of his father, he had a different project of society.

He became known as Frederick the Great and was nicknamed Der Alte Fritz (Old Fritz) by the Prussian people and, eventually, the rest of Germany.

Facts About Frederick The Great

- Born: 24 January 1712, Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, (Present-day Germany)

- Full name: Frederick II or Frederick the Great

- Nickname: Der Alte Fritz (Old Fritz)

- Known For: Enlightenment Ideas and Military Reforms

- Reign: 31 May 1740 – 17 August 1786

- Predecessor: Frederick William I

- Successor: Frederick William II

- Spouse: Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

- Nationality: German, Prussian

- House: Hohenzollern

- Religion: Calvinism

- Father: Frederick William I of Prussia

- Mother: Sophia Dorothea of Hanover

- Death: 17 August 1786, (aged 74), Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia

- Cause of Death: Asthma, Gout, and other Ailments

- Burial: Sanssouci, Potsdam

Frederick The Great Biography

Frederick II was born in Berlin on January 24, 1712, son of Frederick William I of Prussia and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, he was baptized with the sole name Friedrich. Frederick’s birth is welcomed by his grandfather, Frederick I of Prussia, with a little more emphasis than usual, as two of his grandchildren had died at an early age.

On his death, in 1713, Frederick William I becomes the new king and Frederick becomes the crown prince. The new king wants his sons and daughters to be educated as ordinary people and not as royalty, so Frederick’s education is entrusted to a Huguenot governess, with whom he simultaneously learns French and German.

However, despite his father’s wish that his upbringing is entirely religious and pragmatic, Federico leans toward French literature and other intellectual concerns. With the help of his tutor, Jacques Egide Duhan de Jandun (1685–1746), Frederick obtains a secret 3,000-volume library of poetry, Greek and Roman literature, and French philosophy, with which he supplements his official lessons.

In addition, we are encouraged by his mother and tutors to correspond with philosophers of the Enlightenment, which contrasts with its rejection of the discipline of the Court and the Prussian military traditions.

Although his father, Frederick William I, is a devout Lutheran, he fears its own fundamental dogma: unconditional election. To prevent this thought from causing problems in the way of thinking of his son, Frederick William I orders that he not be taught anything related to the ideas of Calvinism, especially that the word predestination should not even be mentioned.

Despite the fact that Frederick is not very devoted, he does end up adopting the same Calvinist ideas, despite his father’s efforts. Some historians consider that he could take this drift, precisely, to contradict him.

Frederick The Great Reign

Frederick the Great acceded to the throne at 28 years of age. A new chapter in the life of Frederick II and European history begins after the death of Frederick William I on May 31, 1740.

At the time of his accession to the throne as King in Prussia in 1740, Prussia was made up of a variety of separate territories, including the Duchy of Cleves, the County of Mark, and the County of Ravensberg, west of the Holy Roman Empire; the Margraviate of Brandenburg, West Pomerania and Central Pomerania, east of the Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia (the former Duchy of Prussia), outside the Empire and bordering the Republic of Two Nations.

The title King in Prussia referred to the dominion exclusively over the old Duchy, and Frederick would declare himself King of Prussia from 1772, after having acquired much of the rest of the Prussian region.

During his long reign (1740 to 1786) he became an exponent of enlightened despotism, in which he introduced some reforms inspired by this trend. It promotes the codification of Prussian law, according to the principle that the law must protect the weakest: abolition of torture, judicial independence.

It encourages colonization based on immigrants from the most depopulated and backward areas of the kingdom. Practice customs protectionism for your industry. In his military campaigns, his great capacity and vision, tactics, and strategy stand out, so much so that he is considered one of the greatest military geniuses in all of history, and that he is even compared to Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, or Napoleon I.

Frederick The Great Military Reforms

In 1740, when he ascended the Austrian throne Maria Teresa, daughter of the emperor Charles VI, Frederick II invaded Silesia, taking advantage of the moment when Austria was especially vulnerable, taking possession of this territory by the Battle of Mollwitz.