Pompeii was an ancient city located near Naples, Southern Italy. The Empire extends from Spain to the Black Sea, from Britannia (United Kingdom) to Egypt. After the year of four emperors, 69 CE, Rome has been under the firm and stable rule of Emperor Vespasian for ten years.

The Emperor has just started building the Flavian Amphitheatre, which will be known as Colosseum. For the moment, you are content with your own local gladiatorial shows in an Arena that can sit half the population of your rich and beautiful town.

Pompeii, and Herculaneum, the Roman town that in August of 79 CE was destroyed by one of the most devastating volcanic eruptions of ancient times. The city was buried under 4 to 6 meters (13 to 20 ft) of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Archaeological excavations have been carried out since the 18th century. Since then, large parts of the city have been uncovered and the site gives a well-preserved picture of Roman daily life. Pompeii is on the World Heritage List of UNESCO and is a major tourist attraction that attracts more than 2.5 million visitors annually.

We are going to discover what was life like before the disaster, how did the explosion happen and what is the legacy of a city buried by ashes, but frozen in time.

Pompeii Facts

- Founded: 7th–6th century BC

- Location: Pompei, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy

- Region: Europe

- Official name:-

Archaeological Areas of Pompeii

Herculaneum

Torre Annunziata - Type: Settlement

- Designated as world heritage site: In 1997

- Area: 64 to 67 ha (170 acres)

- Population: 20,000

- Language: Osco, Greek, Latin

- Abandoned: 79 AD

- Cause: Destroyed by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD

History of Pompeii

The area where Pompeii was founded was particularly attractive to settlers thanks to a favorable climate and rich soil. Especially suitable for growing olives and grapes, which are still important produce of the region.

Little did the Romans know that the richness of this soil was volcanic in nature and was due to a long-forgotten eruption of the now innocent-looking mountain over-shadowing the area, Mount Vesuvius.

This eruption occurred around 1800 BC; several archaeological sites, especially one near Nola, reveal the destruction of Bronze Age settlements. But its memory was lost and the Romans knew nothing. In fact, their civilization may have never witnessed directly a volcanic explosion.

However, in Greek mythology, there is at least a hint of the power of Vesuvius: according to legend, it was here that Herakles – or ‘Hercules’ for the Romans – had fought giants in a fiery landscape. It is not by chance if the nearby town Herculaneum, destroyed alongside Pompeii, was named after this heroic episode.

In addition, Roman historian Servius wrote that the name Pompeii itself derived from the word ‘pumpe’. This means a procession in honor of Hercules’ victory over the giants. Following the Bronze Age settlements, the next steady settlers of the region were Greek colonizers, present from the 8th century BCE until 474 BCE.

The Samnite Period

From then on, the Samnite people from the surrounding mountains began to infiltrate and dominate the region. The Samnite expansion soon attracted the attention of Rome.

Taking advantage of their infighting, the Romans defeated them in the Samnite Wars from 343 to 290 BCE, eventually taking over what is today the Campania region.

The Roman period

The Romans took a liking to Pompeii, and what’s not to like about a seaside town on the Gulf of Naples, ripe with olives and wine? In the II Century BCE, the town flourished with large building projects.

However, the Pompeiians took the habit of rebelling against the central power of Rome, until Consul Sulla besieged the town in 80 BCE and re-settled 5,000 legionaries in the town. You know, just to keep an eye on them. As the century ended, Pompeii enters its period of peak prosperity.

A local senate was established, and a new amphitheater was built with a capacity for 5000 spectators. Pompeii used to cover an area of three square kilometers, that’s about 1.3 square miles, without counting the outer suburbs, plus hundreds of villas and farms in the countryside.

The population of the town had been estimated at between 15,000 to 20,000, one-third of them being slaves. Twice as many people would have lived in the surrounding farms and villas. About these villas: they were grandiose, many of them with panoramic views of the Gulf.

This coast was a sort of playground for the Roman elite, in fact, even notorious Emperor Nero is thought to enjoy some prime real estate near Pompeii. His wife, Poppaea Sabina was a native of the town after all.

Pompeii Economic

But Pompeii was not just a fancy resort, it served a very important function: its port was one of the more important on the Gulf of Naples, from where local produce was shipped to the farthest locations of the Empire. Pompeiians exported olive oil, wine, wool, salt, walnuts, figs, almonds, cherries, apricots, onions, cabbages, and wheat.

On the other hand, they imported exotic fruit, spices, giant clams, silk, sandalwood, wild animals for the arena, and, very importantly, slaves. As you have heard most of the trade involved food and we know that the Pompeiians treated themselves pretty well.

They were particularly fond of beef, pork, oysters, shellfish, artichokes well the list goes on. Beyond the port, the town itself was bustling with activity, as we can deduct from the variety of buildings which included shops of all kinds, gyms, baths, a market hall, and a disproportionate amount of brothels.

But the most striking of all these buildings were the patrician houses. Many of them had been decorated with magnificent floor mosaics and wall paintings that depict all manner of scenes from myths to daily life such as religion, industry, and very often, the sexual habits of the residents.

Many of the larger villas also had a permanent triclinium or eating area, in the garden. Ten of them even had systems of small canals running between the diners so that as dishes floated past they could take their pick of the delicacies on offer.

In complete contrast to the richer residences, archaeologists have also dug out the slave quarters: cramped, unsanitary, and prison-like dwellings, often not far from curtained cubicles where lower-class prostitutes worked their trade.

Signs of Doom (63-79 AD)

By the summer of 79 AD, the Pompeiians had little reason to think that a catastrophe was looming. And why would they? The economy of the gulf was booming and the holiday villas of the rich brought constant investment. And yet, the preceding years were rife with signs that could have warned them of impending disaster.

The Romans were constantly worried about predicting the future by observing ‘portents’ in the shape of strange sights and sounds, or unusual births. But only a few years earlier, there had been far less mysterious signs, only they did not know how to interpret them.

Philosopher Seneca, the advisor to the emperor Nero, was writing a treatise on the causes of Pompeii earthquakes in 63 CE, when a catastrophic seism hit the Campania region, causing extensive damage to both Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Seneca’s theory was that earthquakes in different parts of the world were all interconnected and that they could be caused by stormy weather. But of course, he did not have the scientific means to link them with volcanic activity.

He downplayed this danger, going as far as chastising the landowners who were deserting Campania for fear of further earthquakes. The damage of the earthquake in 63 CE was so bad that entire houses were demolished and reduced to agricultural land.

Other houses were still standing in 79 CE, but their doors to the top floors had been boarded up, indicating a fear that higher floors may still collapse. But, probably to the approval of Seneca, most of the population did not abandon Pompeii.

Damaged houses were still being repaired and redecorated in 79 CE, and there was an extensive program to restore public buildings in the Forum of Pompeii. The earth did not shake only in 63 CE, though.

Archaeologists have pieced together clues that indicate that further earthquakes took place in the weeks or possibly just days before the eruption. For example, an open trench was found by a water tower, indicating that a shock may have damaged the water supply, and repair works were ongoing.

Moreover, many of the houses excavated show signs of repair and redecoration work: heaps of plaster, pots, and building tools. A simple, prosaic image. Which suddenly, in this context turns into the tragic frozen picture of a population undeterred by disaster, dedicated to repairing their damage, unaware of what was to come.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius erupted on the 24th of August, 79 CE, or possibly on the 24th of October according to recent findings. The eruption lasted for more than 24 hours. At first, it manifested itself as a giant column of thick smoke, which was actually combined with tons of ash, volcanic rock known as pumice, and lithic debris.

All these materials subsequently rained over Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum. According to some accounts, this rain was not necessarily lethal, while according to other studies their accumulated weight resulted in the collapse of several houses, crushing its inhabitants to death.

Some of the Pompeiians fled at once, and they did the right thing. Think about their perspective: this was the first time in living memory that somebody had experienced such a sight. For all they knew, this was the work of the wrath of the Gods.

Many others, thought that their best chance was to seek a robust shelter and wait for the mysterious clouds to clear. Among them, two who would make and write history. They were Pliny the elder, and his nephew, Pliny the younger. The Elder, was a celebrated author, a successful administrator, a scientist, and a naval commander.

At that time he was serving as the commander of the Misenum fleet stationed in Campania. His decision to stay was not motivated only by ill-judged self-preservation. He had an intense scientific curiosity which may have led him initially to stay in Pompeii, to observe this unseen phenomenon.

But soon he realized the dangers for the population and he put his ships at their service, conducting relief efforts for the evacuation of the Pompeiians. His nephew the Younger, barely 18 on that day would also become an author and a public official.

In his lifetime, he wrote a collection of private letters that illustrate in detail the public and private life in the Roman Empire. Amongst the few survivors of Pompeii, Pliny the Younger wrote the only surviving eyewitness account of the eruption in a letter to his friend Tacitus, an orator and historian.

In his writings, he tells of the valiant efforts led by his uncle to save the citizens from destruction, and how this caused his death by asphyxiation. The rain of ashes may have caused the structural collapse, but for sure it had thickened the air around Pompeii, making it almost impossible to breathe.

Particles of ash clung to the airways, clogging nostrils, throats, lungs. While standing on the deck of his ships and giving orders to help, Pliny the Elder slowly collapsed. He simply lay down on the deck of his boat and died. But the worst was yet to come.

Around midnight, the column of smoke and ash above Vesuvius, also known as an eruptive column, collapsed. This caused the first pyroclastic surge. Inlay terms, a pyroclastic surge is an avalanche of volcanic material, a massive wave of hot ash, rock fragments, and gas rushing down the slopes of a volcano.

And now the surge is traveling faster than 100 km – or 60 miles – per hour towards the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum, burning the face of the earth once rich and prosperous, a tidal wave of unknown fears, finally unleashed. Hundreds of refugees were seeking shelter in the vaulted arcades by the seaside.

They were catching their possessions. They were murmuring prayers to the Gods. Mothers whispering to their children, dragged from their beds and still asleep. The arcades were carved in stone, facing away from Vesuvius, giving them a sense of safety.

When the surge reached them, they were exposed to the intense heat of 500 degrees Celsius, or 900 degrees Fahrenheit. The passing of the surge lasted for 150 seconds. They had been dead for 149 of them. In its destructive path, nature knows how to be swift and merciful, and it did not wake up the children.

Forensic experts analyzed the skulls of the victims and consistently noticed holes in their temples. They deduced that the intense heat of the surge had caused the brains to immediately melt, and then to boil, eventually bursting out of the skulls due to extreme pressure.

The flesh of the citizens had been also suddenly vaporized, bursting into a red mist which then deposited on their bones. It was as if the Pompeiians had been caught in a storm of fire and blood raining from a lacerated sky. And this was only the first wave.

A hail of pumice had covered the streets in a layer at times as thick as 3 meters (10ft) when subsequent surges strafed the few survivors who were fleeing in the dark or hiding beneath roofs. Many of the bodies were burned to their bones or completely consumed by fire.

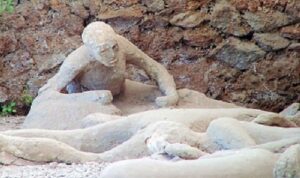

Most of the deceased were covered in layers of ash and lithics, like frozen images of their immediate demise. Some of these corpses were found with their arms raised, close to the mouth, like boxers.

This had led archaeologists to believe that they were defending themselves against attackers or covering their airways – which led to believe that asphyxiation was the leading cause of death.

Instead, this pose was found to be another consequence of extreme temperatures: sudden heat can in fact cause the muscles of the arms to contract, the fists are clenched and raised close to the head.

How many people died in the Pompeii Vesuvius eruption?

It is impossible to tell. But surely the death toll was in the tens of thousands. The Romans were accustomed to huge losses of life in battle, and even they regarded this catastrophe as exceptional.

The corpses found in Pompeii or Herculaneum were only a fraction of all the victims: the destruction spread to the entire area south of Vesuvius and onto the Sorrentine peninsula. Many more died in the countryside, and even at sea, in the last attempt to sail to safety.

Pompeii Ruins

The effects of the eruption were traumatic. The same resilient people who had rebuilt their cities after the previous earthquakes failed to reoccupy the sites involved in the destruction. Pompeii remained a ghost town, inhabited only by looters.

The tunnels they excavated are still visible today. Room after room of the city’s buildings had holes hacked through the walls by tunnellers, and extensively sacked. The cities on the north of the Gulf of Naples swiftly recovered, especially the port of Puteoli continued to be a significant commercial center.

The coast continued to attract rich holidaymakers but never again regained the popularity it had before the disaster when it was Rome’s playground. It took 18 centuries for the area to flourish again when Naples became an attractive capital under the Bourbon kings.

The rich courtiers and ambassadors of that time built their villas on the Gulf, bringing new life to the region. The aristocrats of Europe established the tradition of the Grand Tour, and the hidden treasures of the Gulf of Naples attracted international fascination.

Pompeii Rediscovery

The rediscovery of Pompeii was finally re-discovered in 1755 CE when work on the construction of the Sarno Canal began. Under just a few meters of volcanic debris, diggers were surprised to find an entire town.

From then on, Pompeii became an essential destination for Grand Tour-ers, attracting such famous visitors as Goethe, Mozart, and Stendhal. Besides architectural remains, scholars of Pompeii were presented with a treasure trove of rare historical artifacts providing a unique window into the past.

Archaeologists found an ingenious process to take plaster casts of the impressions left by the dead in the volcanic material. These eerie casts can still be seen today in Pompeii. Some of them, as we mentioned earlier, look like boxers who have just been knocked down.

Some are crouching, may be seeking shelter. Others, looked as though they had been surprised in their sleep. The analysis of the casts and the skeletons has provided evidence of the health and lifestyle of ancient Pompeiians.

For example, bad teeth were a common problem! Tooth decay was rife due to an over-sweet diet, and enamel was worn away by stone chips in bread. Tuberculosis and malaria were also prevalent. But the saddest find is the skeletal remains of slaves. Often, they were found still chained, unable to escape the disaster.

Their bones also show very clearly the signs of malnutrition, chronic arthritis, and deformity caused by overwork. It has also been possible to reconstruct the daily life of the town thanks to the scores of written records preserved at the site.

These take the form of thousands of electoral notices and hundreds of wax tablets, mainly dealing with financial transactions. Other sources include signs, graffiti, and tomb inscriptions, which give an insight into sections of society that Romans considered to be of lower standing: slaves, women, gladiators.

All of them are usually ignored in surviving books and legal records. The graffiti in particular offer a joyous view of the ordinary lives of ordinary people, which offers a refreshing contrast to the tragedy of the eruption, and remind us that this archaeological site was once inhabited by people, rather than skeletons or plaster casts.

One romantic graffiti, in a private house, tells us that “Secundus says hello to his Prima, wherever she is. I ask, my mistress, that you love me” Not all inscriptions are so heartfelt. This one, outside another house, issues a warning to a very rude citizen: “To the one defecating here. Beware of the curse. If you look down on this curse, may you have an angry Jupiter for an enemy!”

Scrounging patrons at the tavern of Salvius is told: “Whoever wants to serve themselves can go on and drink from the sea” At the Inn of the Mule-drivers: “We have wet the bed, host. I confess we have done wrong. If you want to know why there was no chamber pot”

In the barracks of the gladiators, we learn that: “Floronius, privileged soldier of the 7th legion, was here. The women did not know of his presence. Only six women came to know, too few for such a stallion.”

And a very bored gladiator wrote: “On April 19th I made bread”. Feather in a tavern of Herculaneum a series of inscriptions tell the story of the two BFFs, Apelles and Dexter. The first night they write: “Two friends were here. While they were, they had bad service in every way from a guy named Epaphroditus. They threw him out and spent 105 and a half sestertii most agreeably on whores”.

They then return looking for a better service “Apelles the chamberlain with Dexter, a slave of Caesar, ate here most agreeably and had an SCR*w at the same time” These guys are becoming regulars, as we read that: “Apelles Mus and his brother Dexter each pleasurably had sex with two girls, twice”.

The Meaning of a Tragedy

Pompeii and Herculaneum are some of the biggest and best tourist attractions in Italy, and if you are lucky enough to travel south of Rome, I strongly recommend that you pay a visit.

Pompeii in a way was a microcosm representing the whole of the Roman civilization, with its amphitheater, the Legionnaires, the gladiators, the villas for the rich, and the slums for the slaves.

If we were to look for some kind of sense in the blind wrath of the natural disaster that destroyed it, well, this could be a symbol that even when nearing its peak, the Empire was not guaranteed to be eternal.

Or, we could say that the Gods had decided to punish the hubris of these mortals, whose expanding power was based on the tainted foundations of slavery and moral corruption. But, sometimes, even when the harshest tragedies occur, there simply is no reason, they just happen.

It is up to us to provide meaning, by remembering and celebrating what could have been lost forever. Pompeii, like a giant time capsule preserved in ash for centuries, gives us a perfect opportunity to do just that.

People Also Ask

- When was Pompeii destroyed?

Pompeii was destroyed in 79 AD - Which volcano destroyed Pompeii?

Mount Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii - What exactly happened in Pompeii?

Pompeii was a Roman town that in August of 79 CE was destroyed by one of the most devastating volcanic eruptions of Mount Vesuvius in ancient times. - Is Vesuvius still active?

Yes, Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano in mainland Europe, which is located on the west coast of Italy. - Are there still dead bodies in Pompeii?

Yes, Pompeii still contains the dead bodies of more than 100 people preserved as plaster casts. Some of these corpses were found with their arms raised, close to the mouth, like boxers. - When was Pompeii discovered?

Pompeii was discovered in 1755 CE when work on the construction of the Sarno Canal began. Under just a few meters of volcanic debris, diggers were surprised to find an entire ancient town.