Olive Oatman (Born on September 7, 1837 – Died on March 21, 1903) was a woman come from the state of Illinois. Whose family was killed in 1851, when she was fourteen, by the Native Americans, presumably the Tolkepayas (western Yavapai).

They captured Olive Oatman and her little sister and made them their slaves, before selling them after a year to the Mohave people. She spent several years among the Mohaves, where she and her sister were treated well, but the latter starved to death during a period of famine. Olive returned to the Whites five years after being captured.

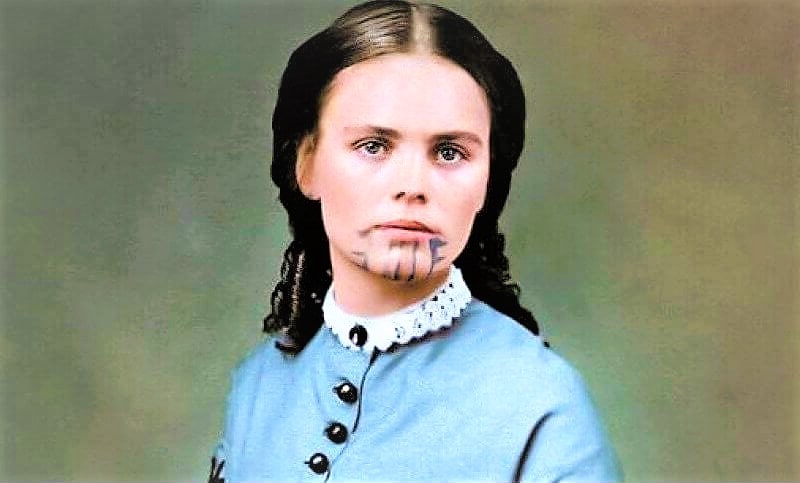

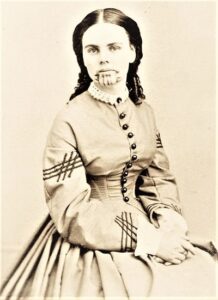

The life of Olive Oatman inspired many books, plays, films, and poets. His story had a huge impact on the media of the time. The blue facial tattoo she had received from the Mohaves was impressive. She never gave a truly comprehensive account of her life among Native Americans, and many rumors circulated.

Quick Facts Of Olive Oatman

- Born: September 7, 1837, LaHarpe, Illinois, U.S.

- Real Name: Olive Ann Oatman

- Nickname: Olive Oatman Fairchild, Oach

- Parents: Father – Royce Oatman and Mother – Mary Ann Oatman

- Spouse: John Brant Fairchild (m. 1865–1903)

- Daughter: Mary Elizabeth “Mamie” Fairchild

- Siblings: Mary Ann Oatman, Lorenzo D. Oatman, Royce Oatman, Jr., Lucy Oatman, Charity Ann Oatman, Roland Oatman

- Nationality: United States

- Books:- 1. Captivity of the Oatman Girls;

2. Being an Interesting Narrative of Life Among the Apache and Mohave Indians, Etc.

3. Twenty-Fifth Thousand. – Scholar’s Choice Edition - Died: March 21, 1903 (aged 65) Sherman, Texas, U.S.

- Place of burial: West Hill Cemetery, Sherman, Texas, United States

Early Life Of Olive Oatman

Born to Royce Oatman and Mary Ann Oatman. Olive was one of seven children and was raised according to the customs of the Mormon religion. Olive Oatman daughter name is Mary Elizabeth “Mamie” Fairchild.

In 1850, the Oatman family joined the convoys led by James Brewster, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose disagreements with church leaders in Salt Lake City, Utah, caused him to sever ties with Brigham Young followers in Utah and lead his followers. (The Brewsters) to California, which he argued, unlike Utah, is the “designated gathering place” for Mormons.

The number of immigrants who left Independence with Brewster on August 5, 1850, ranged from 85 to 93. Provoked divisions within the group split about Santa Fe (territory of New Mexico).

Followers of the Brewster took a northerly route, while Royce Oatman and several other families took a southerly route through Socorro (New Mexico) and Tucson (Arizona). Near Socorro, Royce Oatman led a group of travelers.

They reached the territory of New Mexico in early 1851, but the climate conditions in this territory did not satisfy them. The rest of the transports gradually gave up on reaching the mouth of the Colorado River.

The group reached the oasis of Maricopa Wells when there was talk of a barren wasteland and hostile Indians as they moved forward. The rest of the families decided to stay. Ultimately, no one but the Oatman’s continued their journey.

Later, on the territory of modern Arizona, what is commonly called the “Oatman Massacre” happened on the banks of the Gila River, about 80-90 miles east of Yuma.

The Oatman Massacre

Mary Ann and Royce Oatman had seven children. Mary Ann was also pregnant with their eighth child during their journey from Illinois to the Gila River. The Oatman children ranged in age from 17-years-old to 1-year-old, with Lucy Oatman being the oldest.

On the Oatman’s’ fourth day out from Maricopa Wells, they were approached by a group of Native Americans who were asking for tobacco and food. Due to the lack of supplies, Royce Oatman was hesitant to share too much with the small party of Yavapais.

They became irate at his stinginess. During the encounter, the Yavapais attacked the Oatman family. The Yavapais clubbed the family to death. All were killed except for three of the children: Lorenzo, age 15 (who was left for dead), Olive, age 14, and Mary Ann, age 7, who were taken to be slaves for the Yavapais.